Medical Editor: Dr. David Cox, PhD, ABPP

What is the default mode network?

Although it only makes up 2% of the body’s weight, the brain uses 20% of the body’s energy. Even when it may seem like we aren’t “using” our brains, there is a lot of activity going on in there.

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is a large, highly connected network of brain regions. It’s what kicks in when attention isn’t focused on anything, in particular, thus the name “default.”

Discovered accidentally in 2001 by Marcus Raichle, a neurobiologist at Washington University, the DMN is considered the “me network.” Although many areas of the brain are involved in this network, the medial prefrontal cortex (MPC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), and the inferior parietal lobe (IPL) are primary ones. fMRI scans show that these parts of the brain light up when daydreaming and reflecting or ruminating about the past or future. The functions of this network have a strong self-referential component, connecting memory and self. Not only does this include self-reflection, but also self-criticism.

It shouldn’t be a surprise, then, that the DMN is associated with such mental health conditions as depression, anxiety, and OCD. Research has even shown that patients with chronic pain experience higher DMN activity while ruminating about their pain. This is likely due to increased functional connectivity (or hyperactivity), leading to excessive rumination and negatively skewed perspective and memory recall.

The Task Positive Network (TPN) is a system in the brain that regulates cognitive functions such as decision making, focused attention, and working memory. There appears to be a seesaw-like relationship between the DMN and the TPN, called TPN/DMN synchronization, which gets activated when we take on tasks that command attention and focus. When the DMN turns on, the TPN turns off, and vice versa. Conditions such as ADHD interfere with this synchronization.

How do psychedelics affect the default mode network?

Psilocybin-containing mushrooms (sometimes called magic mushrooms or shrooms), LSD (acid), dimethyl-tryptamine (DMT), and mescaline (a compound found in the San Pedro and peyote cactus) are some commonly known psychedelics.

These classic psychedelics work primarily by binding to serotonin receptors in the brain, mimicking serotonin, which is associated with mood and feelings of well-being. Neuroimaging studies have shown that psychedelics decrease activity in the DMN, allowing for new neurological connections. This may be one underpinning of the creativity-enhancing effect that psychedelics have for some people.

Shutting down the DMN also has positive mental health implications, especially conditions that involve rigid thinking patterns. Specifically, the DMN gives rise to what is commonly called ego, or the narrative “self.” Psychedelics, typically at higher doses, have been shown to catalyze ego distortion for some people, even ego-dissolution. These medicines can both “quiet the brain chatter” of the DMN and increase connectivity to create new solutions to the problems of the mind (such as ruminations).

Psychedelic experiences can be profound. People often describe subjective feelings of being “one with everything.” This feeling of connection can have positive outcomes for people, even after the psychedelic trip is over. This may be due to a “resetting” to the DMN, creating antidepressant effects. Simply seeing that things can be different can profoundly change mental health outcomes.

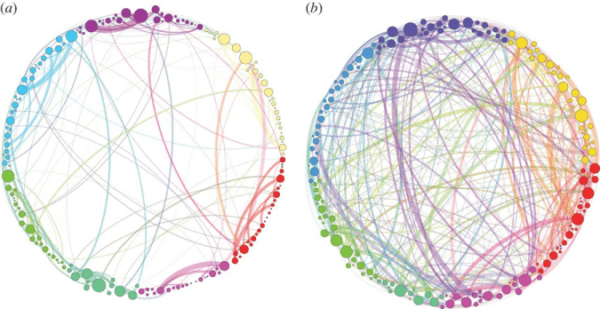

Neuroscientist Robin Carhart-Harris and psychopharmacologist David McNutt decided to try using psychedelics to explore human consciousness more deeply. They injected study participants with LSD and psilocybin and then studied their brains under fMRI imaging. The image below is from this Imperial College study.

The brain on the left, the placebo, shows a normal, well-ordered brain. In contrast, the one on the right, after psilocybin injection, shows vast cross-linking of networks, indicating greater communication across the brain as a whole. The brain seems to become (at least temporarily) more interconnected and less specialized long enough to create new perspectives, insights, and meanings while the DMN is temporarily pulled off-line.

This greater communication is what Carhart-Harris refers to as “the entropic brain.” In science, higher entropy is typically synonymous with increased disorder (or chaos). Looking at this increase in the context of psychedelic use allows for a return to more primitive, or primary, states of consciousness.

Imagine a toddler exploring the world, taking in new information rapidly. Normally, the DMN lowers entropy (creating the state of normal waking consciousness that is typical in adulthood), filtering out much of this information. Imagine what new solutions and insights are possible in this state, with existing self and world narratives temporarily put aside.

Conclusion

Modern science is only beginning to scratch the surface of understanding the mind and body and how they work together to create consciousness. Research into the DMN and how psychedelics change brain connectivity has added to the body of modern knowledge about mental illness, but we still have a long way to go. Activities that decrease DMN activity, such as meditation, may be beneficial for people who struggle with self-criticism and rumination. Psychedelic therapies should consider how DMN state suppression could be further utilized to promote psychological healing and well-being, both during and after the trip.